Peace be Upon You

This week, we light the second Advent candle – the candle symbolising peace. In Donna Koh’s article titled ‘Peace be Upon You’, she reflects on the meaning of “home” in a world where people move far, far away for a multitude of reasons. She shares how love, joy, and hope seeped through the cracks of a dark and difficult year to bring her closer to God.

…

The month of December is the season of Advent. We think of the birth of Jesus, and look forward to the festive celebrations with our loved ones. We may find ourselves more pensive than usual, looking back on the year that has passed and taking stock of the highs and the lows. This year, I am in a more sombre mood. Instead of the birth of Christ, I am distracted and wonder instead about what Mother Mary’s experience must have been like all those years ago. Scholars tell us that Joseph and Mary’s journey from Nazareth to Bethlehem must have been more arduous than accounts let on. Did she ever feel out of place? Would she have felt indignant or embarrassed throughout her travels and delivery? Did she long to return home amidst her discomfort, short- term as she knew the travel for the census would be? Exponentially more sobering for me this season is the fact that horrific violence continues to rage on at the time of writing, just under 100 kilometres away from the very location Mary and Joseph would have trudged through and where Jesus was born in Bethlehem. Unrest and tension are rife elsewhere in the world too. How did we allow sacred lands to turn into a place of strife, contempt and bloodshed? How do we sit and watch as people lose their homes to violence? Time may have changed physical and political landscapes, but surely the human capacity to feel is timeless and enduring. Life in Singapore is cushy, so perhaps it is difficult to empathise with people whose experiences are so far removed from ours. But imagine what happens when you wake up to the unfamiliar. Imagine losing your home and everything you know, with no end in sight. What does this do to your identity? It does not feel right to celebrate this year. Perhaps I am extra sensitive this year because I too, am not home among the familiar. I too, am in limbo.

The hum of the fridge is my daily companion in the quietest parts of the day when everyone I know and miss in Singapore is asleep, 13 hours ahead of my location. I look up sometimes to realise that it has begun snowing again. To tropical humidity-weary Singaporeans and in the holiday glow, winter is enticing and snow is novel. No one seems to mention how traffic turns snow into a muddy slush that you have to wade ankle-deep in, or how snow turns everything into the most morose canvas that will make you ache for sun-drenched Singapore. Forget shorts and flip-flops: you will spend 10 minutes putting on multiple layers to transform into the Michelin Man just to get to the supermarket down the road. Sunlight will become a rarity. And no one will mention how the decision to take a break from work and stay overseas for a while can cripple you with the keenest grief you have ever experienced. But this was my reality for the first five months of 2023.

In our world of extremes, work and rest lie worlds apart and never the twain shall meet unless we have earned both the money and the right to go on holiday. But off I went with four pieces of luggage in tow to a city I had never visited, taking a break from work in the form of unpaid leave. At the Toronto-Pearson International Airport, the customs and immigration officer demanded to know why I would be staying so long in the city, disapproval and suspicion lacing every question. “If you knew my passport and my country, you wouldn’t ask me those questions,” I seethed in my heart, despite knowing that the officer was only doing his job. It was the first of many self-induced affronts I would come to experience, most probably my form of self-defence against the apparent illogic of leaving Singapore. Sometimes, friendly Canadians would strike up a conversation, their expressions faltering before they asked me to repeat myself. How unfair— I would think to myself— that popular culture has made your accent so instantly recognisable and decipherable to me, and, where I’m from, your intonation and sentence stress would be deemed inaccurate. Do you know where I’m from, I sometimes wanted to scream. You don’t even know me, I always wanted to cry. For five months, I felt like a ghost— invisible and identity-less, unless someone deigned to chat with me at the gym or at a cafe. I missed the buzz of work and professional conversations that gave me heady rushes of satisfaction; the predictable Singapore weather; my mother’s love language of cutting fruits after dinner; having afternoon toast and coffee with my parents at our neighbourhood mall. I missed the reliability of our public transport; face-to-face heartfelt conversations with friends and colleagues that never had a moment’s awkward silence; the familiarity of knowing where to go for anything and everything without ever needing a map. I had thought myself an intrepid traveller— I had hiked in different countries alone; flown 36 hours to South America and passed through three different airports, alone; navigated cities on my mobile phone. Yet it all felt very different this time round. I was tourist no more. I was a short-term resident who had arrived when drug-related assaults were on the rise. Here, cannabis stores are common and addicts shuffle half-naked in a drugged-out stupor on the streets and on public transport, oblivious to the cold. I couldn’t return home after a mere three weeks away and amble back from the airport the way I used to, souvenirs and exhilarating travel anecdotes in hand. Taking unpaid leave meant that there was nothing I could return to, and nothing to occupy my time in Toronto. In one fell swoop I had arranged the most unique arrangement for myself, ever: no job, no friends and family within a 7,000km radius, no familiar surroundings or environment. It was a sobering jolt to my system. It seemed like only I could answer those questions I longed others to answer: do I know where I’m from? Do I know who I am? Am I still me when away from my country and all who know me, and without my job and its soul-sapping but so-satisfying responsibilities?

So who are we when we don’t have our country, loved ones, or routines to remind us who we are and what we are capable of doing? Far away from home, I found myself stricken by the thought of cooking, but persevered, telling myself that if my mother can cook anything and everything, then this same culinary prowess must be in my DNA, ready to unleash itself with more practice. So, I made fried rice, pizza, dumplings, mee hoon kway and so many other dishes from scratch, and like any Asian woman who calls the shots in the kitchen, complained about how my cooking tasted in order to hear gushing compliments from those eating my food. I brought kaya croissants (store-bought from the only Singapore-style cafe here; I am not at that fusion-baker level yet) to my CrossFit gym so that the Lebanese, Irish and Canadian owners could taste something from my home country; unable to write work emails or plan programmes, I resorted to meal-planning and grocery-budgeting for “intellectual stimulation” (they were underwhelming); I attended French classes, panicking from the student’s seat every time the teacher gave us a Kahoot! quiz (but not before teaching my classmates how to use Kahoot!, like the trained teacher I am); I made friends with people from parts of the world (Mexico, Argentina, Australia, Hong Kong, Canada of course, and etc) whom I would never have gotten the chance to get close to while in Singapore, some of whom have become my Toronto family; and any time I could, I talked about my home and my work, pretending not to convulse with pride when people raved about our airport, our national carrier, our education system, and more. And little by little, as I strove to feel connected to what felt like a previous life, I found more lightness in my heart. I thought I was moving away and moving on, but it turns out that knowing where you come from and appreciating how it has shaped you is every bit as important.

What about residents or refugees who have been wrested from the familiar and thrust into an alien landscape? Homesick as I was, I have never seen and delighted in true diversity and inclusivity until I lived in Toronto. Residents really have come from every corner of the world, I hear tongues completely unfamiliar to me, and wealth does not segregate as distinctly. At times, I walk past wizened Asian men and a part of me longs to ask “Uncle, why are you so far away from home?”. But time and again, I encounter someone who looks Asian by ethnicity and am always confounded to hear a torrent of North American-accented English spilling out of their mouth. They have clearly grown up here, might even have been born here, and I quickly learn how presumptuous I am to have assumed that Toronto isn’t home for them. Most of the time, people move for better opportunities, with hope and a dogged determination that life will turn out better. But what happens when you are forced to flee your country? What happens when you were displaced? Over here, I marvel at how people’s backgrounds and life choices are accepted without question nor judgement. Near my house is an Orthodox Church, where both the Canada and Ukraine flag proudly adorn the entrance. In the Old Town, there is a banner hung outside the Anglican Cathedral which welcomes same-sex marriages to be conducted and celebrated there. Toronto is a city that people come to for a myriad of good reasons, and I have learnt that people don’t always leave for greener pastures. Sometimes they leave out of necessity, even driven by fear. I am not a refugee by far, but this year my heart lies with the many people in the world who have lost their homes, do not feel at home, and yearn for home. I remember Mosa, the tall, dashing grandfather who had driven me around when I was a tourist in Jordan and who had plied me with maamoul after the one time I had some and raved about it. He had fled to Jordan from Palestine as a young man, and I remember the silence when he pointed out his homeland from the car, within sight across the wadi. I have learned that we can have many homes, that home can be a feeling as much as it is a place, and that making a home lies in our hands.

So, this isn’t a feel-good piece of writing that brings immediate good tidings. I write from uncertainty and loss instead, away from the easy and the good, having put myself in a space where I have struggled to find myself and stand up for what I want. But I also write with thanksgiving, hope, and faith. This year has been exceptionally challenging for me, and I have spent many days in tears and darkness — both literally (the sun sets at 4 p.m in winter) and figuratively. Yet I cannot be more grateful to recall the kindness and care shown to me by others— messages from friends and ex-colleagues in the middle of my loneliest, quietest days that remind me who I am and where I am from; invitations from friends in Toronto that assure me that I am capable of making new and lasting friendships; stories shared with me by others who have had similar experiences to mine, and commiserating with these like-minded friends. God sent me so many angels to support me through the year, for whom I will be forever thankful. Other fierce reminders of His presence and mercy took several forms: basking in the warmth of the elusive sun on hikes; visiting churches that welcomed me with open arms; the endless patience that Canadians demonstrate, be it while waiting in line or traffic; getting stopped for directions by strangers which boosted my morale to no end as I imagined being able to pass off as a Toronto local. I had encountered the legendary Canadian kindness, and learnt that people have the power to make you feel at home too. When you are in a dark place, even the smallest act of kindness feels like the blazing sun.

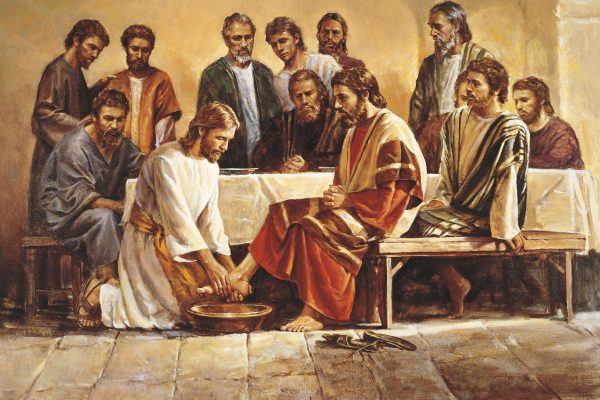

Lastly, I write this thinking of victims, refugees, the lost and the lonely, and people wading their way through pain, worry or grief today. And if you, reader, are not at Peace as well, I believe that Hope, Joy and Love will be your balm. In John 14:27, we are assured by God that “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not be afraid.” It is Advent after all, and even if we feel the absence of one symbol, trust that the combination and confluence of the other three will bring us out of the darkness. God has placed us exactly where we need to be. All we have to do is trust Him. Besides, after every winter, ice thaws, the cold relents, and in their place, light always beckons. Jesus Christ our Saviour is born.