For many who graduate from school, what endures beyond the grades and accolades is friendship. True friends share in each other’s joys and support one another through challenging times; they help each other grow in virtue, knowledge and maturity. St John Bosco, an educator of street urchins and founder of the Salesians, counselled:

“Fly from bad companions as from the bite of a poisonous snake. If you keep good companions, I can assure you that you will one day rejoice with the blessed in Heaven; whereas if you keep with those who are bad, you will become bad yourself, and you will be in danger of losing your soul.”

Pope John Paul II, born Karol Józef Wojtyła – whose feast is on 22 October, the day of his papal inauguration – knew the importance of friendship as a young man. The German Nazis and Russian communists invaded Poland during his university days in 1939; the university was shut down and he was forced to work as a manual labourer, quarrying limestone. During that time, he met Jan Tyranowski, assigned by a Salesian priest as a student mentor. Jan introduced Karol to the Living Rosary youth groups, which continued to meet throughout World War II, keeping the faith while their priests were imprisoned.

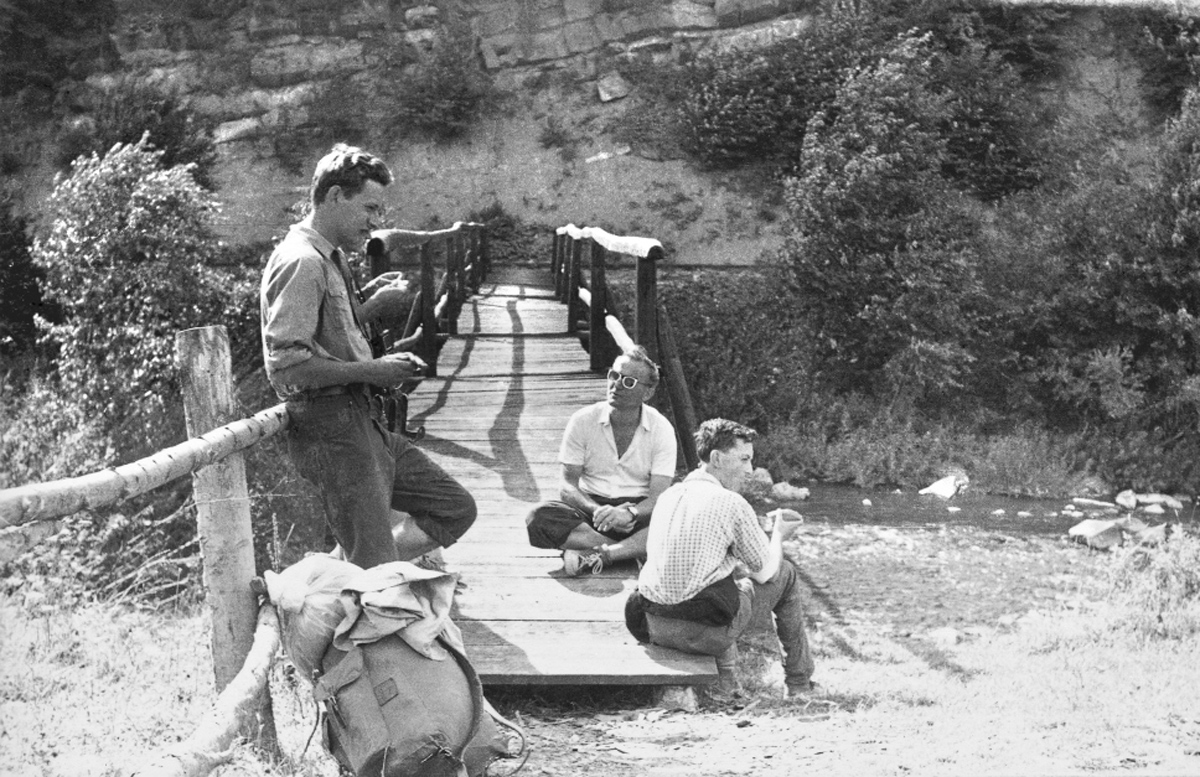

Karol soon discerned a vocation to the priesthood, and Jan managed to attend his ordination on 1 November 1946 before dying of tuberculosis. As a young priest, Fr Wojtyła formed youth groups as his friend Jan had. These young men and women went hiking, attended retreats, and put on plays, despite being in a war zone. In these groups, the youth found freedom which was denied them by the oppressive regime which had seized control of all institutions, including schools. Through the apostolate of friendship, they were able to cultivate human flourishing in the midst of violent turmoil, helping one another grow holistically.

A young John Paul on a hiking trip. Source: voiceofthesouthwest.org

The word “friend” comes from a Proto-Indo-European word meaning “to love”. Pope John Paul II wrote in his book Love and Responsibility:

“Friendship, as has been said, consists in a full commitment of the will to another person with a view to that person’s good.”

This echoes St Thomas Aquinas, who said, “Love is to will the good of another.”

In fact, what Jan and Fr Wojtyła did reflected what Jesus Himself did during His earthly mission. He gathered a group of friends around Him (John 15:15), teaching them about God the Father through His words and actions. These friends of Christ spread the Word of God throughout the world, inviting each of us today to join them in becoming friends of God. The most effective evangelisation is based on a solid foundation of friendship, where one receives the love of God through a friend. How can you share God’s love with your friends today?

He wrote: “We should live in a state of complete dependence on grace, and however great the gifts and effects it produces, we should always focus on God Who is its source. As to our good deeds, we should remember that it is God Who deigns to act through us.”

He wrote: “We should live in a state of complete dependence on grace, and however great the gifts and effects it produces, we should always focus on God Who is its source. As to our good deeds, we should remember that it is God Who deigns to act through us.”